IN DEFENSE OF GENERAL LEE

By Edward C. Smith[Dr. Smith is co-director of the Civil War Institute at American University in Washington, D.C.]

Let me begin on a personal note. I am a 56-year-old, third-generation, African American Washingtonian who is a graduate of the D.C. public schools and who happens also to be a great admirer of Robert E. Lee’s.

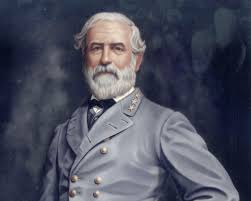

Today, Lee, who surrendered his troops to Gen. Ulysses S. Grant at Appomattox Court House 134 years ago, is under attack by people — black and white — who have incorrectly characterized him as a traitorous, slaveholding racist. He was recently besieged in Richmond by those opposed to having his portrait displayed prominently in a new park.

My first visit to Lee’s former home, now Arlington National Cemetery, came when I was 12 years old, and it had a profound and lasting effect on me. Since then I have visited the cemetery hundreds of times searching for grave sites and conducting study tours for the Smithsonian Institution and various other groups interested in learning more about Lee and his family as well as many others buried at Arlington.

Lee’s life story is in some ways the story of early America. He was born in 1807 to a loving mother, whom he adored. His relationship with his father, Henry “Light Horse Harry” Lee, (who was George Washington’s chief of staff during the Revolutionary War) was strained at best. Thus, as he matured in years, Lee adopted Washington (who had died in 1799) as a father figure and patterned his life after him. Two of Lee’s ancestors signed the Declaration of Independence, and his wife, Mary Custis, was George Washington’s foster great-granddaughter.

Lee was a top-of-the-class graduate of West Point, a Mexican War hero and superintendent of West Point. I can think of no family for which the Union meant as much as it did for his.

But it is important to remember that the 13 colonies that became 13 states reserved for themselves a tremendous amount of political autonomy. In pre-Civil War America, most citizens’ first loyalty went to their state and the local community in which they lived. Referring to the United States of America in the singular is a purely post-Civil War phenomenon.

All this should help explain why Lee declined command of the Union forces — by Abraham Lincoln — after the firing on Fort Sumter. After much agonizing, he resigned his commission in the Union army and became a Confederate commander, fighting in defense of Virginia, which at the outbreak of the war possessed the largest population of free blacks (more than 60,000) of any Southern state.

Lee never owned a single slave, because he felt that slavery was morally reprehensible. He even opposed secession. (His slaveholding was confined to the period when he managed the estate of his late father-in-law, who had willed eventual freedom for all of his slaves.)

Regarding the institution, it’s useful to remember that slavery was not abolished in the nation’s capital until April 1862, when the country was in the second year of the war. The final draft of the Emancipation Proclamation was not written until September 1862, to take effect the following Jan. 1, and it was intended to apply only to those slave states that had left the Union.

Lincoln’s preeminent ally, Frederick Douglass, was deeply disturbed by these limitations but determined that it was necessary to suppress his disappointment and “take what we can get now and go for the rest later.” The “rest” came after the war.

Martin Luther King Jr. was one of the few civil rights leaders who clearly understood that the era of the 1960s was a distant echo of the 1860s, and thus he read deeply into Civil War literature. He came to admire and respect Lee, and to this day, no member of his family, former associate or fellow activist that I know of has protested the fact that in Virginia Dr. King’s birthday — a federal holiday — is officially celebrated as “Robert E. Lee-Stonewall Jackson-Martin Luther King Day.”

Lee is memorialized with a statue in the U.S. Capitol and in stained glass in the Washington Cathedral.

It is indeed ironic that he has long been embraced by the city he fought against and yet has now encountered some degree of rejection in the city he fought for.

In any event, his most fitting memorial is in Lexington, Va.: a living institution where he spent his final five years. There the much-esteemed general metamorphosed into a teacher, becoming the president of small, debt-ridden Washington College, which now stands as the well-endowed Washington and Lee University.

It was in Lexington that he made a most poignant remark a few months before his death. “Before and during the War Between the States I was a Virginian,” he said. “After the war I became an American.”

I have been teaching college students for 30 years, and learned early in my career that the twin maladies of ignorance and misinformation are not incurable diseases. The antidote for them is simply to make a lifelong commitment to reading widely and deeply. I recommend it for anyone who would make judgment on figures from the past, including Robert E. Lee.